Dark and early one winter morning in New York, Wythe Marschall and I embarked on a quest to find a microorganism—a genetically engineered chimaera—that could turn itself into a living photograph. We intended to join Dr. Natalie Kuldell’s bacterial photography class at MIT. Undaunted by a 3:45am departure time from the Port Authority, unhalted by a bus wreck in Connecticut, and aided by four cups of coffee we arrived just in time for the 11am class.

On the chalkboard, Natalie rapidly outlined the design principles we would be exploring to create the living photographs. First she drew an electrical circuit. She explained that these design principles were a simple, electronics-derived way of depicting the series of biochemical reactions that would occur within the living photograph. Essentially, we would introduce a light sensitive gene (from photosynthetic blue-green algae) into a strain of E.coli that cause the bacteria to create a black pigment. Red light would activate the mechanism, and bacteria in areas of the dark areas of the photo would digest a certain kind of sugar (S-gal®) that would cause a blackish color to be produced from the bacteria.

Now it was time for the hands-on portion of the class. To further support the biology-as-electronics analogy, the class used a breadboard and LEDs to show how the bio chemical reactions would create the circuits. Natalie mused, “If only biology were are predictable as electronics.”

After everyone had tested their breadboards, it was time to create the actual bacterial photographs. Using pipettes we followed the protocols that had been outlined to create the photoreceptive E.coli. Each Petri dish’s bacteria was suspended in liquid agar to assure adequate distribution, creating a lawn for the bacteria to grow evenly.

A little about the development of these protocols: photosynthetic bacteria created from a dual biological circuit system designed by Dr. Chris Voigt, then an assistant chemistry professor at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), now also at MIT. The idea further developed by a group of students at the University of Texas at Austin, as part of the iGEM (intercollegiate Genetically Engineered Machine) competition in 2005 at MIT. (http://2006.igem.org/wiki/index.php/University_of_Texas_2006)

Petri dishes in hand, we selected images to be printed on transparencies. This creates a shaded area that allows the bacteria beneath to activate and produce the sugar-digesting enzyme (beta-galactosidase) that creates the darks in the Petri dish. The UT students explained it nicely (http://www.utexas.edu/features/2005/bacteria/index.html), “When the bacteria grow in dark parts of the Petri dish, they digest the sugar and produce black pigment. Those in the light don’t produce the sugar-digesting enzyme and the film remains clear.”

Students selected a penguin, the Taj Mahal, even a petite handlebar mustache. Wythe selected an octopus rendering from the legendary botanist and artist Ernest Haeckel, and I pulled a dotted unicorn that I had created on my computer. After all images had been loaded onto the thumb drive, Wythe and I accompanied Natalie to the lab where her bacterial darkroom was located.

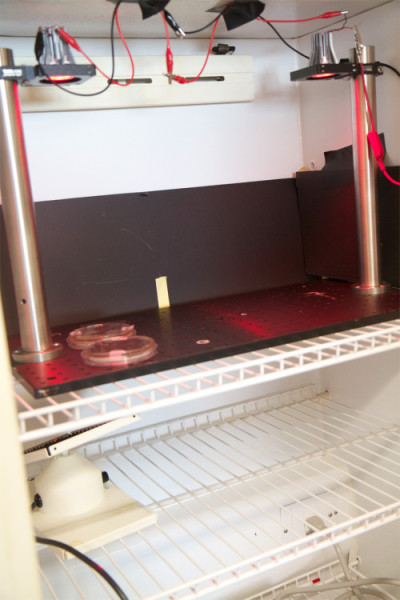

Natalie experimented many years to create the perfect “darkroom” for the bacterial cultures. Identifying the combination of the perfect distance and light intensity was no speedy feat. Her darkroom is constructed in a refrigerator outfitted with a red light and shelving for the Petri dishes to sit on. The outside of the refrigerator is covered with post cards from distant places; monuments to great achievements in beauty and construction from both humans and nature. The gothic Duomo di Milano, the majestic Grand Canyon, a gorgeous selection of Central and South American coastlines… even a Texan cowboy, perhaps a nod to the UT students. Our octopus and unicorn petri dishes safely tucked into the bacterial darkroom, we thanked Natalie and bid her farewell.

Simultaneously exhausted and enlivened, Wythe and I boarded the bus back to New York, chatting the entire journey back about the wonders of biotechnology.

Two days later we received an email from Natalie with several photos of bacterial photography from the class. There, imprinted in the agar were the students’ selections; the Taj Mahal, the penguin, the mustache. Sadly though, we were not bacteria-whispers. Our little microbes precipitated neither fish nor fauna… no octopus, no unicorn. So what had happened? Somewhere we made an error; a fine measurement in the protocols was off—perhaps we had too much of one thing and not enough of another. Who knows? We’ll get it next time!

Resources:

About bacterial photography:

http://www.utexas.edu/features/2005/bacteria/index.html

http://2006.igem.org/wiki/index.php/University_of_Texas_2006

About Natalie Kuldell:

http://web.mit.edu/be/people/kuldell.shtml

http://www.biobuilder.org/

Special thanks to Daniel Gruskin for arranging the visit, and Oliver Medvedik for his suggestions on the diagram.